|

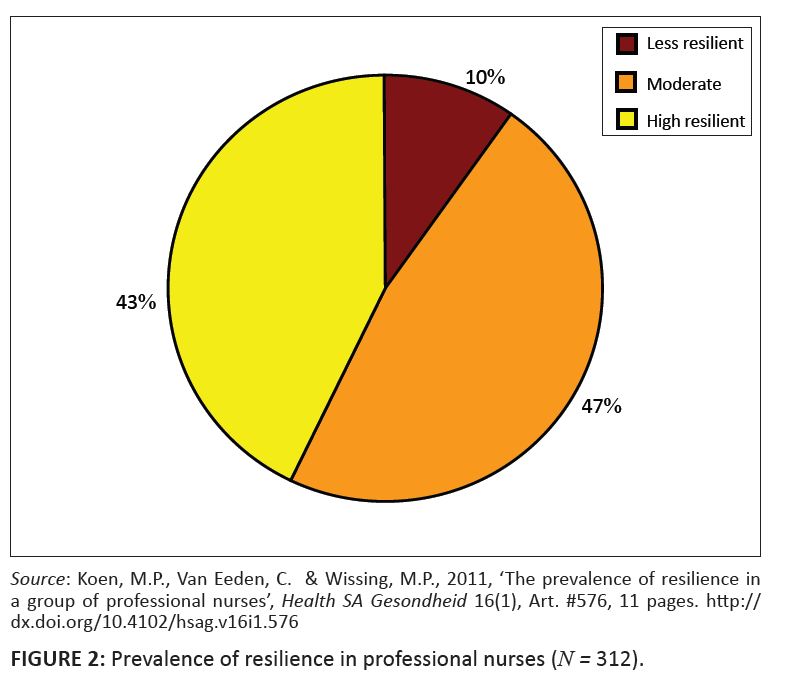

The literature and practice show that many professional nurses feel emotionally overloaded and are experiencing job dissatisfaction, which often results in them leaving the profession. Paradoxically, some nurses choose to remain in nursing and survive, cope and even thrive despite their unique workplace adversities. It is, however, not known what the prevalence of resilience amongst nurses is, and what influence working in private versus public contexts has on this resilience. The aims of this study were to determine the prevalence of resilience in a group of professional nurses, to determine whether private versus public contexts played a role in nurses’ resilience, and to obtain an indication of participants’ views of their profession and resilience therein. A cross-sectional survey design was used where professional nurses (N = 312) working in public and private hospitals in South Africa voluntarily completed measures of psycho-social well-being as indicators of their degree of resilience. They also answered three open-ended questions on their profession. Results showed moderate-to-high correlations amongst scales, indicating conceptual coherence as indicators of resilience. Prevalence of resilience was determined by normalising the mean scores of the measuring instruments. The total value of the normalised mean scores was given as a fraction (0−1), representing a level of resilience manifested by the participants across all scales. This indicated three levels of resilience: 10% of participants manifested low resilience, 47% moderate resilience and 43% high resilience. Nurses in private health care had significantly (small practical effect) higher levels of resilience than nurses in public health care.

Die literatuur en praktyk dui daarop dat baie professionele verpleegkundiges emosioneel uitgeput is, werksontevredenheid ervaar en dikwels die beroep verlaat. Paradoksaal kies sommige verpleegkundiges om in die beroep te bly, en floreer selfs ten spyte van hul unieke en moeilike werksomstandighede. Dit is egter niebekend wat die voorkoms van veerkragtigheid in verpleegkundiges is nie, of wat die invloed van werk in privaat versus die openbare omgewing op veerkragtigheid is nie. Die doelwitte van die studie was om die voorkoms van veerkragtigheid in ‘n groep professionele verpleegkundiges te bepaal, om die rol van privaat versus openbare omgewings in veerkragtigheid te bepaal, en om ‘n aanduiding van deelnemers se siening oor hul professie en veerkragtigheid daarin, te bekom. ‘nDwarsdeursnit ontwerp was gebruik waarin professionele verpleegkundiges (N = 312) werksaam in openbare of privaat hospitale in Suid-Afrika vrywillig vraelyste oor psigososiale welstand as aanduiders van die vlak van veerkragtigheid, voltooi het. Hulle het ook drie oop-einde vrae oor hul beroep beantwoord. Bevindinge het op matige tot hoë korrelasies tussen skale gewys wat dui op konseptuele koherensie tussen die indikatore van veerkragtigheid. Veerkragtigheid is bereken deurnormalisering van die gemiddelde tellings vir die meetinstrumente van al die skale. Die totale waarde van genormaliseerde gemiddeldes was as ‘n fraksie (0−1) uitgedruk. Drie vlakke van veerkragtigheid het gemanifesteer, 10% van die deelnemers het met lae veerkragtigheid gemanifesteer, 47% met matige veerkragtigheid en 43% met hoё veerkragtigheid. Verpleegkundiges in privaat gesondheidsorg het beduidende (klein praktiese waarde) hoёr vlakke van veerkragtigheid getoon asverpleegkundiges in openbare gesondheidsorg.

Problem statement

Research and practice indicate that many professional nurses feel emotionally overloaded and are experiencing job dissatisfaction, especially those in the public sector (Ehlers 2006). However, although many nurses consider leaving the profession, some resiliently survive, cope and even thrive despite the workplace adversity experienced. It is, however, not known what the prevalence of resilience amongst nurses is, what the role of private versus public contexts is, and what the implications for the health care system are. In the last 5–10 years there has been a shift in health care, from a fragmented, mainly curative, hospital-based service to an integrated, primary health care (PHC), community-based service in South Africa (African National Congress 1994; Geyer, Naude & Sithole 2002). The health care system currently consists of a private and a public sector, with the private sector being profitable as clients have medical insurance paying for services, whilst the public sector is a State-owned system which is publicly funded and free to unemployed citizens or available for a small fee to those able to pay (Geyer et al. 2002; Van Rensburg & Pelser 2004). The public sector is divided into national, provincial and district systems with professional nurses involved at all three levels, whilst predominantly health care providers work at the provincial and district levels (Dennill, King & Swanepoel 2002). These changes have had far-reaching effects on the work context of professional nurses, as larger sections of the population have now become able to afford or obtain services for free (Pelser, Ngwena & Summerton 2004). The resultant increase in health care utilisation places a great burden on nurses, especially those in the public sector; the vast financial and human resource disparities between the public and private health care sectors have adverse effects on the working conditions of these professionals (Day & Gray 2005). Public sector nurses carry the burden of serving the majority of South Africa’s population with minimal funds and insufficient personnel. In this sector 58.9% of nurses are serving 82% of the population, resulting in an increase in workload, a shortage of equipment and supplies, overcrowding in clinics, poor working conditions, poor staff morale, deterioration in quality care and abuse of scarce resources (Van Rensburg & Pelser 2004; Walker & Gilson 2004). Furthermore, the critical nurse shortage in South Africa – with an estimated shortage of 32 000 (Oulton 2006) – has become alarming, with a total of 47 390 800 patients served by 101 295 professional nurses in 2006, a ratio of 468 patients for 1 nurse according to the South African Nursing Council (2006). This shortage is partly due to emigration of nurses but also the result of low wages, heavy workloads, poor working and living conditions, lack of resources, limited career opportunities, poor management of health services, unstable work environments and economic instability, and the impact of HIV and AIDS (Bateman 2005; Buchan 2006). Previous research reported that professional nurses feel emotionally overloaded, stressed, fatigued, helpless, hopeless, angry, shocked, grieved, irritated, fearful, unsettled, frustrated, and were experiencing job dissatisfaction, moral distress and lack of personal accomplishment – and for these reasons often left the profession (Aiken, Clarke & Sloane 2001; Pillay 2009; Shisana et al. 2004; Smit 2004; Van den Berg et al. 2006).

Nursing context

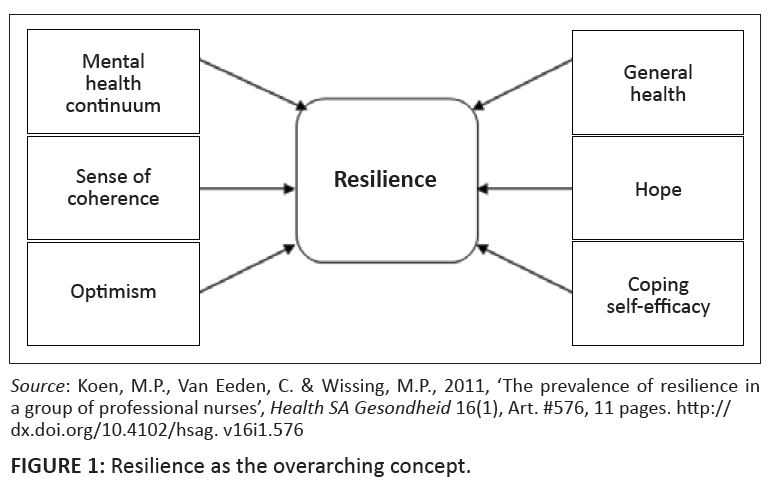

South Africa’s health care is dependent on caring, compassionate, professional nurses as the backbone of the health care system, being the first point of contact for patients and with PHC services mainly provided by these nurses (Ntuli & Day 2004; Van Rensburg & Pelser 2004). Professional nurses need to find satisfaction and meaning in their work in order to be successful care-givers, able to care for patients and model health care behaviours (Vander Zyl 2002). It is therefore necessary to address the resilience and well-being of nurses in order to enable these nurses and the organisations they serve to promote personal satisfaction and resilience and enhance productivity (Keyes 2007; Nelson & Simmons 2002; Ryff & Singer 2003; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi 2000). Information about the prevalence of resilience and positive psycho-social functioning in professional nurses could indicate the nature and magnitude of the problem and the need for interventions. Research on human resilience has been done in order to understand how certain individuals, when faced with challenges and risk factors or stressors, are able to recover without psychological harm and develop into confident, competent, caring adults (Huber & Mathy 2002). Resilience has become an appealing concept because of its roots in theoretical models of positive psychology that seek to explore factors that enable individuals to successfully overcome adversity (Kaplan 1999). Just as there are multiple risk factors or stressors in given situations, there are multiple indicators of positive adaptation. Research by Richardson (2002) indicates that resilient individuals have the potential not only to return to previous levels of functioning after experiencing adversity, but manifest gains in self-esteem, self-efficacy, autonomy and a change in life perspective that serve to make them stronger than they were before. Such gains in adaptive behaviour have been termed thriving or flourishing (Carver 1998; Keyes 2006b; Ryff & Singer 2003). Garmezy (1991) defined resilience as ‘the capacity for recovery and maintained adaptive behaviour that may follow initial threat or incapacity upon initiating a stressful event’ or ‘manifest competence despite exposure to significant stressors’ (Glantz & Johnson 1999). Resilience is a multi-dimensional construct and is used in this study as an overarching umbrella term operationalised by measures of specific facets of psycho-social well-being. These facets were identified from the literature and previous research. For the purposes of this study resilience is conceptualised in terms of high levels of hope, optimism, coping self-efficacy, sense of coherence and flourishing mental health – all described in the literature as characteristics of resilient people (Kaplan 1999; Lifton 1993; London 1993; Risher & Stopper 1999; Seligman 1998). These constructs are described in brief below. Coping self-efficacy: Coping refers to efforts to deal with something difficult, and these efforts may include cognitive, behavioural or psychosocial strategies that an individual uses to alleviate stress when events challenge the routine predictions of the world (Kleinke 1998). Constructive coping is seen as a characteristic of resilient people when making the effort to manage situations that they appraise as potentially stressful or harmful (Kleinke 1998; Lazarus & Folkman 1984; Zeidner & Endler1996). Self-efficacy refers to beliefs about having the capabilities to organise and perform tasks successfully within a specific domain, thereby influencing the outcome of circumstances (Bandura 1997). Bandura also indicated that self-efficacy convictions influence resilience to adversity. Chesney et al. (2006) combined the coping and self-efficacy concepts and introduced the coping self-efficacy construct (and measuring instrument). Coping self-efficacy refers to a person’s perceived ability to cope effectively with life challenges or threats. Like Bandura, Chesney et al. (2006) indicate that beliefs about one’s ability to perform specific coping behaviours or coping self-efficacy would influence the outcomes of adverse situations. In the current study, coping self-efficacy refers to the belief of the professional nurses that they could perform coping behaviour that would succeed in dealing with the work stresses they encountered. Sense of coherence: This refers to the extent to which individuals see life issues as manageable, understandable, and meaningful, and therefore expectations that things will mostly work out well. Antonovsky (1979, 1987) defined it as a global orientation that expresses the extent to which an individual has a pervasive, enduring though dynamic conviction that the stimuli deriving from his or her internal and external environments in the course of living are structured, predictable and explicable, that the resources are available to meet the demands posed by these stimuli, and that these demands are challenges worthy of investment and engagement. Sense of coherence is linked to a variety of coping mechanisms and/or characteristics of a person that can facilitate effective tension management, andcan thus be associated with the construct resilience (Eriksson & Lindström, 2006; Kinman, 2008). In the current study it refers to the ability to view demands in the nursing workplace as challenges, finding meaning in them and coping with stressors with the help of available resources. Optimism: This refers to a global expectation that things will turn out well. According to Scheier, Carver and Bridges (1994), optimistic individuals are able to pursue their valued goals in the face of difficulties, using effective coping skills and experiencing less intense negative emotions when encountering obstacles. Optimism is associated with good health, active coping styles and good occupational adjustment, which are characteristics of resilient people (Carr 2004). In this study it refers tothe ability to maintain an optimistic explanatory style regarding difficulties in the nursing profession, and to be able to positively adjust. Hope: This refers to the ability to plan pathways to reach desired goals despite obstacles, and the motivation to use these pathways. Hope is closely related tooptimism and conceptualised by Snyder (2000) as involving two main components: pathway thoughts that formulate positive goal outcomes and agency thoughts that create efficacy expectations to reach the goals. Resilient individuals can apply hope features to adapt to change, accept challenges and cope with adversity. In this study hope refers to professional nurses who are able to set realistic goals in the nursing profession and find the ways and will to achieve these despite difficulties they may encounter. Flourishing mental health: Mental health can be described on a continuum, with optimal mental health characterised as flourishing with high levels of well-being at one end and mental ill health, with low levels of well-being or languishing at the other, and moderate mental health in between. Keyes (2002) indicated that flourishing individuals have enthusiasm for life and are actively and productively engaged with others and in social institutions. Flourishing is a state of wholeness where a person can deal with stressors in an effective way and maintain wholeness when interacting with their environment in a positive way (Keyes 2002). Resilient professional nurses need mental and physical health when interacting with the demanding nursing workplace in a positive way (Keyes 2002). Resilient nurses would be closer to the flourishing end than the moderate or low mental health end of the spectrum. The overarching concept of resilience used in this study with the relating concepts and measurement of

aspects of resilience in professional nurses is illustrated in Figure 1. This study explored the prevalence of resilience in professional nurses in South Africa as there is a paucity of information about the concept of resilience as it pertains to nurses in practice. A thorough understanding of the prevalence of resilience in professional nurses and the coping skills and resilient adaptations of such resilient nurses could be of benefit to the health care service. It would provide hospital managers with useful guidelines for in-service training that won’t be threatening and can facilitate growth in professional nurses. The challenge is to identify resilient professional nurses (or the absence of resilience in nurses) and to try to learn from their experiences and functioning in order to fortify strengths and coping skills in others (Glantz & Johnson 1999; Patterson 2002).

|

FIGURE 1: Resilience as the overarching concept.

|

|

Research objectives

This study aimed to determine the prevalence of resilience in a group of professional nurses to determine whether there are significant differences in levels of psychosocial well-being and resilience between participants working in private and public health care facilities, and to obtain an indication of the participants’ view of their profession and the resilience therein. Research significance

There is a paucity of information on resilience as it pertains to nurses. A deeper understanding of resilience can be of theoretical and practical importance (Glantz& Johnson 1999; Patterson 2002). Information obtained could lead to an understanding of the quality of life and well-being of professional nurses and be used to develop specifically targeted interventions. The latter may in turn improve the quality of the overall functioning of professional nurses, thereby enhancing both the quality of nursing care per se as well as improving the health care service overall.

|

Research method and design

|

|

Design

This was primarily a quantitative investigation in which a cross-sectional survey design was used. In such a design the interrelationships amongst variables are assessed. The cross-sectional design is well-suited to descriptive purposes in an investigation (Shaughnessy & Zechmeister, 1997

Research population and sampling

The participants were 312 South African professional nurses who voluntarily agreed to take part in the study and were employed in public and private hospitals and PHC clinics affiliated with the latter. For practical reasons the suburban areas of Krugersdorp, Randfontein and Carletonville in Gauteng and Potchefstroom in the North West province were used for the research. Participants who were professional nurses and able to communicate in English or Afrikaans made up this convenience sample. The socio-demographic data of the participants are presented in Table 1.

|

TABLE 1: The socio-demographic data of professional nurses in this study

(N = 312).

|

Materials

A research booklet was compiled starting with a biographical questionnaire to gather socio-demographic information from the participants and including three open-ended questions on their feelings about the profession and resilience, followed by the seven measuring instruments. The booklet also contained instructions for completion of questionnaires and information about the confidential handling of personal data and explaining the objectives of the study, and a consent form for voluntary participation to be signed by all participants. Six hundred and fifty questionnaires were distributed, 330 were returned and 18 were discarded because they were incomplete; thus 312 (48%) were completed and analysed. Szelényi, Bryant and Lindholm (2005) suggest that a response rate of 32% is acceptable in self-report surveys such as the present one. A description of the scales used is outlined below.

Resiliency Scale (RS)

The RS (Wagnild & Young 1993) is a 25-item scale that measures the degree of individual resilience, which is considered a positive personality characteristic that enhances individual adaptation. All items are scored on a seven-point scale that ranged from 1 = disagree, to 7 = agree. All items are worded positively and reflect accurately verbatim statements made by participants in the initial study on resilience conducted by Wagnild and Young. Possible scores range from 25–175, with higher scores reflecting higher resilience. The authors reported good internal consistency with a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.80 and with test-retest coefficients of0.5–0.98. No previous studies using this scale could be found in South Africa. In a study by Meredith (2005) amongst 105 students at Oxford University in the United Kingdom (UK) a reliability index of 0.89 was reported. In the current study a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.95 was obtained. Mental Health Continuum – Short Form (MHC-SF)

The MHC-SF (Keyes 2005) consists of 14 items which represent three sub-scales, namely Emotional Well-Being (MHC-EWB), Psychological/Personal Well-Being (MHC-PWB) and Social Well-Being (MHC-SWB). To be flourishing, individuals must experience ‘every day’ or ‘almost every day’ at least one of the three signs of hedonic well-being and at least six of the 11 signs of positive functioning during the past two weeks. Individuals who exhibit low levels (never, or once or twice during the past two weeks) on at least one measure of hedonic well-being and low levels on at least six measures of positive functioning are languishing. Individuals who are neither flourishing nor languishing are thought to have moderate mental health. The short form has shown good internal consistency (Cronbach alpha 0.80)and discriminatory validity. Test-retest reliability estimates range from 0.57 to 0.82 for the total scale (Keyes 2007). The three-factor structure of the short form – emotional, psychological, and social well-being – has been confirmed in American representative samples (Keyes 2005, 2009). In a study done in South Africa using the MHC-SF in Setswana-speaking participants, a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.74 was reported (Keyes et al. 2008). In the current study Cronbach alpha indices of0.84, 0.77 and 0.88 were obtained for the subscales with a total scale alpha coefficient of 0.83. The Coping Self-efficacy Scale (CSE)

The CSE (Chesney et al. 2006) is a 13-item measure of one’s confidence in coping behaviours when faced with life challenges. The scale is the short form of the original 26-item CSE measuring coping self-efficacy. The scale has three sub-scales with six items on Problem-Focused Coping (CSE-PFC), four on Stopping Unpleasant Emotions and Thoughts (CSE-SUE) and three on getting Support from Friends and Family (CSE-SFF). Internal consistency and test-retest analyses showed that these factors assess self-efficacy for different types of coping. Predictive validity analyses showed that residualised change scores in using problem- and emotion-focused coping skills were predictive of reduced psychological distress and increased psychological well-being over time (Chesney et al. 2006). In research done in the UK by Chesney et al. (2006), reliability indices of 0.40-0.80 were reported for the CSE with the sub-scales almost identical to this. In a South African study by Wissing et al. (2008) reliability indices of 0.86 and 0.87 for the 26-item version were reported. In the current study Cronbach alpha coefficients of 0.87, 0.89 and 0.79 were found for the sub-scales with a total scale alpha coefficient of 0.85. The Sense of Coherence Scale (SOC)

The SOC (Antonovsky 1987) is a 29-item questionnaire that measures the three dimensions of the sense of coherence construct, viz. comprehensibility, manage ability and meaningfulness. According to Antonovsky, these should not be seen as sub-scales as the SOC was developed to be a unidimensional instrument with three interrelated components. The items are answered on a seven-point semantic differential scale with two anchoring phases. Antonovsky (1993) reported Cronbach alpha coefficients in 29 research studies varying between 0.85 and 0.91. Test-retest reliability studies have found coefficients ranging between 0.41 and 0.97. Studies done in South Africa reported reliability indices of 0.88 (Walker 1999) and 0.85 (Wissing & Van Eeden 2002). In the current study a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.64 was obtained. The Adult Dispositional Hope Scale (HS)

The HS (Snyder, Irving & Anderson 1991) consists of 12 items measuring the self-reported hopefulness trait of an individual, to which participants indicate their responses on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (definitely false) to 4 (definitely true) measuring aspects of hope. Four items of the scale reflect agency (HS-A) (e.g. ‘I energetically pursue my goals’), four items reflect pathways (HS-P) (e.g. ‘even when others get discouraged I can find a way to solve the problem’), and four items are unrelated distracters. Cronbach alpha coefficients for the total score range from 0.74 to 0.84 and test-retest correlations have been 0.80 or above over periods exceeding 10 weeks (Snyder et al. 1991). A study conducted with nurses in Philadelphia, USA, reported a reliability index of 0.61 (Feudtner et al. 2007). Wissing et al. (2008) in a South African study found reliability coefficients ranging from 0.67 to 0.79 for the HS total and the sub-scales. The current study showed Cronbach alpha indices of 0.58 for the HS-P and 0.64 for the HS-A, with an alpha of 0.64 for the HS-Total. Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R)

The LOT-R (Scheier & Carver 1985) was developed to assess individual differences in generalised optimism versus pessimism. This measure has been used in extensive research on the behavioural, affective and health consequences of this personality variable. It is a very brief measure with 10 items that is easy to complete (items 2, 5, 6 and 8 are fillers). Responses to scored items are summed and high values imply optimism. Half of the items are framed in an optimistic manner and half in a pessimistic manner, and participants indicate their extent of agreement or disagreement on a multi-point scale. Scheier and Carver (1985) have reported a high level of reliability (Cronbach alpha of 0.79) and a South African study by Dreyer (2003) reported indices ranging between 0.60 and 0.70. In the current study a Cronbach alpha of 0.59 was obtained for the LOT-R. The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)

The GHQ-12 (Goldberg & Hillier 1979) measures aspects of mental health by assessing symptoms and signs of non-pathological mental ill-being or lack of mental well-being. It consists of four sub-scales: somatic symptoms, anxiety and insomnia, social dysfunction and severe depression. According to Goldberg and Hillier (1979), a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.79 was found for GHQ-12 in the population studied. A study done in Iran with 714 young people showed a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.87 (Montazeri et al. 2003) and a study in South Africa by Bosman (1990) found a reliability coefficient of 0.91. The current study showed a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.84 for the total scale. Open-ended questions

Three open-ended questions were included to establish nurses’ views on how they felt about the nursing profession, whether they consider leaving their job and of so, why, and whether they think they are resilient, and why. Answers were analysed and prominent themes identified. Frequencies of responses were determined.

Data collection

Data were gathered by means of a compiled booklet containing the measuring instruments as discussed above. A pilot study was carried out with 10 participants, who reported that the questionnaires were clear, user-friendly and took about 30 minutes to complete. The Ethics Committee of North-West University approved this study. Permission and written consent were obtained from all stakeholders, namely the Department of Health, the managements of all the partaking facilities and research participants. The principal author presented the intended research project to both the management and supervising professional nurses at all the facilities, explaining the objectives and allowing for questions in order to establish trust in the research process. The initial contact was followed up by phoning and confirming appointments. Supervising professional nurses who attended the initial presentations acted as facilitators and distributed and collected the questionnaires in some facilities; in others they introduced the principal author to participants, and she then personally distributed and collected the questionnaires herself.

Data analysis

The data obtained in this study were analysed by the statistical consultation service of the North-West University in Potchefstroom, South Africa, by means of SPSS for Windows version 17 (SPSS, 2005). Descriptive statistics and Cronbach alpha reliability coefficients were determined for all scales and sub-scales used. Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to determine the validity of the scales. Correlations amongst scales were determined by means of Pearson product moment coefficients and significant differences between subgroups were calculated with t-tests. Prevalence of resilience was determined across measures by normalising the mean scores of the measuring instruments and expressing the total value of the normalised mean scores as a fraction (0−1), representing a level of resilience manifested by the participants across all scales with the following cut-off points: low resilience =< 0.4; moderate resilience = > 0.4; and < 0.6; high resilience = > 0.6. Flourishing, as measured with the MHC-SF, was determined according to the criteria described by Keyes (2006a). Answers to open-ended questions were analysed and quantified according to the following: question 1 – positive and negative feelings; question 2 – yes or no answers and the alternatives given; and question 3 – resilient or not and alternatives as well as reasons or explanations given.

The results are discussed with reference to descriptive statistics, reliability and validity of the measuring instruments, correlations between measuring instruments, the prevalence of resilience in the professional nurses, significance of differences between participants from private and public health facilities, and findings from the open-ended questions.

Descriptive statistics, reliability and validity of instruments

The descriptive statistics and Cronbach alpha reliability indices for all scales are presented in Table 2. The mean scores and standard deviations found in this study mostly corresponded with those found in the literature, which suggests that this group of participants is not very different from the general population in terms of their mental health.

|

TABLE 2: Descriptive statistics and internal consistency indices of the measuring instruments for the total group (N = 312).

|

Correlations amongst measures

The correlations shown in Table 3 between scales and sub-scales used to measure aspects of resilience in this study ranged from moderate to high. The significant positive correlations between the scales and sub-scales (RS, MHC-SF, CSE, SOC, HS, GHQ-12 and LOT-R) indicate that the underlying constructs have features in common on an empirical level which is, for the purposes of this study, conceptualised as resilience. These findings link to those of Gillespie (2007), who found that self-efficacy, hope, coping and stress management were good predictors of resilience in a group of nurses. The significant negative correlations of the GHQ-12 with all the other scales and sub-scales supports what is theoretically expected, namely that resilient professional nurses would have low levels of mental ill-being and dysphoria.

|

TABLE 3: Correlations between all the measuring instruments for the total group (N = 312).

|

Prevalence of levels of resilience across measures

The findings are outlined below using the statistical categories described above. The prevalence of resilience in the total group of professional nurses (N = 312) was as follows: 30 participants (10%) seemed less resilient, 149 participants (47%) seemed moderately resilient, and 133 participants (43%) seemed to be highly resilient. These findings are illustrated in Figure 2. Amongst public sector nurses (N = 124), 14 participants (11%) manifested low levels of resilience, 68 (55%) manifested moderate resilience, and 42 (34%) manifested high resilience. Amongst private sector and PHC nurses (N = 188), 15 participants (8%) manifested low levels of resilience, 88 (47%) manifested moderate resilience and 85 (45%)manifested high resilience. Levels of mental health (with flourishing as an index of resilience) according to the criteria for a categorical diagnosis specified by Keyes (2002) for the MHC-SF were as follows: total group –languishing 4% (N = 12), moderate mental health 51% (N = 158), and flourishing 45% (N = 142); public sector – languishing 5% (N = 6), moderate mental health 56% (N = 69), and flourishing 40% (N = 49); private sector – languishing 3% (N = 6), moderate mental health 47% (N = 89), and flourishing 50% (N = 93).

|

FIGURE 2: Prevalence of resilience in professional nurses (N = 312).

|

|

Differences in resilience between nurses in public and private hospitals

Significance of differences in resilience (across measures) between participants from the private and public sectors is shown in Table 4. Results show that participants working in private facilities score significantly higher on resilience (RS) and emotional well-being (MHCSF-EWB) than those nurses working in public hospitals. Three questions were asked of each of the participants as part of the biographical questionnaire, and the answers to these are reported under the subheadings below.

|

TABLE 4: Significant differences on the measuring instruments between respondents in public and private hospitals (N = 312).

|

How do you feel about the nursing profession at the moment?

Positive feelings reported by participants focused mostly on the satisfaction or reward they experienced in caring for patients (11%), being good at it (9%), feeling that it is a passion or calling (7%), feeling comfortable or secure (5%), and feeling part of a family (3%). Negative feelings reported by participants were in respect of poor remuneration (24%), followed by staff shortages (18%) and working conditions (17%) (mostly from the public sector) the poor professional image (13%), managerial problems (12%), low morale (11%), lack of recognition (11%), high stress and responsibilities (11%), and abusive patients (5%).

Are you considering leaving the profession, and so, to pursue what else? (Table 5)

Alternatives given by participants here were to start their own business (N = 28), to emigrate (N = 12), ‘unsure’ (N = 15), and early retirement (N = 6); the rest did not say. A cause for concern is that these findings show that 116 (37%) of the nurses wanted to leave, whilst 53 (17%) were considering it, together adding up to more than half of the participating nurses (54%).

|

TABLE 5: Participants’ considering leaving the profession.

|

Do you consider yourself as resilient, and if so, why? (Table 6)

Reasons or explanations that participants gave here were that they had learned to cope (N = 10), they had support (N = 15), help from their religion (N = 8), felt that nursing was a calling (N = 7), led a balanced lifestyle (N = 8), had a positive mind set (N = 8), and felt that it was a choice to be made (N = 5). These self-reported findings on resilience closely correspond with the results of the measuring instruments on resilience, which found that 43% were resilient, whilst 129 (41%) self-reported that they were resilient. The 48 (15%) reporting themselves as not resilient corresponded with the 10% indicated by the questionnaires. The remaining (22%) reported that they did not know and 23% reported ‘sometimes’, which also corresponded with the 47% of participants who obtained moderate scores on the questionnaires. A further refinement of these results showed that in public hospitals 60% of the nurses who saw themselves as resilient indicated that they would remain in the profession, whilst 40% of the non-resilient participants would stay. In the private facilities, 66% of self-reported resilient nurses would stay in the profession, whilst 35% of the non-resilient nurses indicated that they would stay.

|

TABLE 6: Participants’ views on own resilience.

|

In order to conduct the research in an ethical manner, the researcher was guided by various international ethical principles outlined by the Helsinki Declaration(Democratic Nursing Organisation of South Africa 1998), Burns and Grove (2005) and Brink (2006). Special attention was given to ensuring confidentiality, and cognizance was taken of organisations and stakeholders involved in the study, such as the management of the different hospitals. Permission for the study was obtained from the Department of Health in the provinces where the study was conducted as well as the managements of the private and public hospitals used in the study. Informed voluntary consent was obtained from the participants and protection from discomfort and harm were ensured (Brink 2006).

Validity and reliability

The Cronbach alpha reliability indices of all the measuring instruments, as presented in Table 2, are acceptable to good, except for the SOC, HS and LOT-R scales, which also presented with relatively lower reliability indices in other South African studies (Wissing & Van Eeden 2002; Wissing et al. 2008). Construct validity of the measuring instruments was determined by confirmatory factor analyses, which indicated that all scales were valid in this regard and could be used in this research group.

The aims of this investigation were to determine the prevalence of resilience in this group of professional nurses, to determine whether there were significant differences in levels of psycho-social well-being and resilience between participants working in private and public health care facilities, and to obtain an indication of participants’ view of their profession and resilience therein. The main finding was that from 43% to 45% of the participants in the total group could be described as resilient or flourishing as indicated by their scores on questionnaires and answers to open-ended questions. The finding concerning the relatively high prevalence of resilience in this group of professional nurses was surprising, as studies have reported high levels of burnout and stress in nursing staff. Research by Ehlers (2003) on why nurses decide to deregister found that more than 60% of them suffered from burn-out, and that in PHC settings more than 80% of nurses were experiencing exhaustion or compassion fatigue (Ehlers 2006). The prevalence of flourishing in the total group of nurses(45%), as found on the MHC – SF, which corresponds with the percentage of resilient nurses as determined across all measures (43%), is much higher than the 18% of adults found to be flourishing in the USA, as reported by Keyes (2007), or the 20% of an adult African community sample, as reported by Keyes et al. (2008). This finding may suggest two important matters or hypotheses. Firstly, people who enter the nursing profession or who have survived the difficult nursing context thus far are generally more resilient than people in the general population. The strengths of nurses in general that allows them to function in such a way need to be explored further, especially by means of a qualitative approach. Secondly, the current finding of a relatively high percentage of nurses who are flourishing, together with findings from previous studies that indicated high levels of burn-out in nurses, may provide support for the hypothesised two-dimensional nature of psychological health (Keyes 2005, 2006a): pathology and well-being are two separate although correlated dimensions of human functioning, which may overlap to some extent. Thus, to some extent symptoms of burn-out and symptoms of flourishing may co-exist in some instances in the nursing profession. Although a surprising high number of nurses were flourishing, it should be remembered that 55% were not (57% were not resilient as measured across measures) and may need support and interventions in order to develop higher levels of psychosocial well-being and work satisfaction. The fact that 650 questionnaires were distributed and only 312 (less than 50%) were completed may also indicate the despondence or burn-out experienced by many of these nurses. As far as the private versus public contexts were concerned, participants in private hospitals manifested higher levels of psychosocial well-being than nurses in public hospitals on two of the measuring instruments. However, these differences were, although statistically significant, too small to have an impact in practice as the effect sizes were small. Of importance is the fact that 45% of professional nurses in private hospitals manifested high levels of resilience and flourishing (50%) compared to the 34% resilience and 40% flourishing of professional nurses working in public institutions. However the difference is not statistically significant according to the Chi-square test of independence. A quantification of answers to three questions posed to the participants indicated that 41% saw themselves as resilient in their profession, which is remarkably close to the 43% found in the quantitative data across measures. However, the majority (54%) were considering leaving the nursing profession. Further refinement of the answers indicated that the majority of the nurses who planned to leave the profession were those who self-reported having moderate to low resilience. Of the self-reported resilient participants in both public and private hospitals, 60–63% indicated their commitment to the nursing profession and their willingness to stay. It could be speculated that their resilience enables these nurses to cope with the difficulties posed by the nursing context, and even to attempt to improve the situation from within (to make a difference). Findings also revealed an ageing workforce, with only 22 (7%) aged 30 years and younger, and 230 (72%) older than 40 years. Furthermore, many of the nurses in this study want to leave the profession (116 or 37%) or are considering leaving the profession (53 or 17%), are either ready for retirement, or thinking about early retirement. This is alarming considering the shortage the nursing profession is already facing. Ehlers (2003) indicates that the South African nurse shortage could be exacerbated by the retirement of baby boomers (people born between 1946 and 1964), who constitute more than half of the professional nurses currently registered with the South African Nursing Council. Hindering or negative aspects identified in the nursing context outweighed the positive aspects (which were mostly about a love for nursing), namely poor salaries, staff shortages, poor working conditions, bad professional image, low morale, stressors and responsibilities, managerial problems, lack of recognition and abusive patients. Although all of the participants alluded to these problems in the professional context, nurses working in public hospitals expressed less positive feelings and noticeably more negative feelings about the profession. Various authors (Basson & Van der Merwe 1994; Buchan 2006; Cavanagh 1997; Jackson, Clare & Mannix 2002; Mitchell 2003; Oulton 2006; Tusaie & Dyer 2004) reported on these and similar problems, whilst an emphasis seems to be on financial and managerial problems and lack of recognition or autonomy, a high workload and low morale (Buchan 2006). Fletcher (2001) found in a study with professional nurses that they love the work they do but hate their job, mainly because of adverse working conditions. If this current situation continues, where entry into nursing seems outweighed by exits, with nurses either emigrating or discontinuing practice, the crisis will deepen unless strategies are developed not only to retain nurses but to empower them, attract new recruits into nursing and entice nurses who have left to return to the profession. The current findings on levels of psychosocial well-being and prevalence of resilience in nurses indicate the preciousness of those nurses who are resilient and have stayed in the profession, but also the need to facilitate the psychosocial well-being of the majority of nurses, who are not resilient or flourishing.

There were a number of limitations to this study. The relatively small number of participants (N = 312) was partly caused by the delay in obtaining permission from the Department of Health, which led to two public hospitals not being included in the study. Due to this fact as well as the convenience nature of this sample, the findings should only be generalised to contexts similar to that of the study sample, with caution. At some hospitals management showed a negative attitude to research and did not want the nurses to take part. It seemed that researchers did not report their findings in the past, which made management feel that it is not worthwhile to participate. This should serve as a reminder to future researchers to make results available and go the extra mile to present their findings to the stakeholders involved. The questionnaires were in English, which is a second or third language to most of the participants. For future research these questionnaires could be translated into the main official languages of South Africa.

Based on the findings of this study, the following recommendations are made:

• An investigation under professional nurses who left the profession, to determine reasons for leaving could be beneficial.

• An investigation into healthy work environments for health care professionals is recommended.

• Support systems for health care professionals within the workplace context should be investigated.

• Further research to investigate predictors for resilience in professional nurses and to explore resilience in professional nurses in other settings could be meaningful.

• It is recommended that all the measuring instruments used should be further validated for specific contexts. A new measure of resilience may also be developed through factor analyses on findings from all scales similar to the general well-being component identified across measures by Wissing and Van Eeden (2002).

• The constructs used to represent resilience in this study should not be seen as exclusive, and it is recommended that as many descriptives of resilience as possible in various combinations should be researched to eventually be able to come to a description of resilience as a construct. Factor analysis and structural equation analysis could be used for such research.

In this study resilient professional nurses were identified. Further qualitative in-depth analyses of the experience and functioning of these nurses is proposed; these may provide a thorough understanding of resilience in the nursing profession and help to identify guidelines on which programmes for training and/or interventions for the empowerment of nurses can be based.

The financial support of the National Research Foundation is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed are those of the authors, and cannot be attributed to the NRF. The article is based on a doctoral thesis by the first author that was completed under the supervision of the co-authors.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this paper.

Author contribution

The article is based on a doctoral thesis by M.P.K, who carried out the research under the supervision of C.V.E. and M.P.W.

African National Congress, 1994, ‘A National Health Plan for South Africa’, viewed 25 August 2009, from http://www.bhfglobal.com/files/bhf/Heather%20McLeod%20-%20ANC%20HEALTH%20PLAN%201994.pdf

Aiken, L.H., Clarke, S.P. & Sloane, J.A., 2001, ‘An international perspective on hospital nurse’s work environments: The case for reform’, Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice 4(2),255−263.

Antonovsky, A., 1979, Health, stress and coping. New perspective on mental and physical well-being, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Antonovsky, A., 1987, Unrevealing the mystery of health, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Antonovsky, A., 1993, ‘The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale’, Social Science & Medicine 36, 725−733. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-Z

Bandura, A., 1997, Self-Efficacy, Freeman, New York.

Basson, M.J. & Van der Merwe, T., 1994, ‘Occupational stress and coping in a sample of student nurses’, Curationis 17(4), 35−43.

Bateman, C., 2005, ‘Ethnic tensions aggravate nursing shortage’, South African Medical Journal 95(12), 905−907.

Bosman, J.J., 1990, ‘An investigation into the nature of religious experience and the compilation of a preliminary questionnaire for the empirical measuring thereof’, MA dissertation, Stellenbosch University.

Brink, H., 2006, Fundamentals of research methodology for health care professionals, 2nd edn., revised by C. van der Walt & G. van Rensburg, Juta, Cape Town.

Buchan, J., 2006, ‘The impact of global nursing migration on health service delivery’, Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice7(3), 16−25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1527154406291520

Burns, N. & Grove, S.K., 2005, The practice of nursing research: Conduct, critique, and utilization, 5th edn., Elsevier Saunders, St Louis, MO.

Carr, A., 2004, Positive psychology: The science of happiness and human strengths, Brunner-Routledge, Hove.

Carver, C.S., 1998, ‘Resilience and thriving: Issues, models and linkages’, Journal of Social Issues, 54(2) 245−266.

Cavanagh, S.J., 1997, ‘Educational sources of stress in midwifery students’, Nurse Education Today 17, 128−135.

Chesney, M.A., Neilands, T.B., Chambers, D.B., Taylor, J.M. & Folkman, S., 2006, ‘A validity and reliability study of the coping and self-efficacy scale’, British Journal of Health Psychology 11, 421−437. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/135910705X53155, PMid:16870053, PMCid:1602207

Day, C. & Gray, A., 2005, ‘Health and related factors’, in P. Ijumba & P. Barron (eds.), South African Health Review 2005, pp. 248−366, Health Systems Trust, Durban.

Dennill, K., King, L. & Swanepoel, T., 2002, Aspects of primary health care: Community health care in Southern Africa 2nd edn., Oxford, Cape Town.

Democratic Nursing Organisation of South Africa, 1998, Ethical standards for nurse researchers, Denosa, Pretoria.

Dreyer, J.E., 2003, ‘Die psigologiese- en sosiale welsyn van ‘n groep homoseksuele mans’, MA verhandeling, PU vir CHO, Potchefstroom.

Ehlers, V.J., 2003, ‘Professional nurses’ requests to remove their names from the South African Nursing Councils’s register. Pt. 1; Introduction and literature review’, Health SA Gesondheid 8(2), 63−69.

Ehlers, V.J., 2006, Challenges nurses face in coping with the HIV/AIDS pandemic in Africa. International Journal of Nursing 43, 657. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.11.009, PMid:16436278

Eriksson, M. & Lindström, B., 2006, ‘Validity of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale: A systematic review’, Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 9, 460−466.

Feudtner, C., Santucci, G., Feinstein, J.A., Snyder, C.R., Rourke, M.T. & Kang, T.I., 2007, ‘Hopeful thinking and level of comfort regarding providing pediatric palliative care: A survey of hospital nurses’, Pediatrics 119(1), 186−192.

Fletcher, C.E., 2001, ‘Hospital RN’s job satisfaction and dissatisfactions’, Journal of Nursing Administration31(6), 324−331. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005110-200106000-00011

Garmezy, N., 1991, ‘Resiliency and vulnerability to adverse developmental outcomes associated with poverty’, American Behavioral Scientist 34(4), 416−430. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0002764291034004003

Geyer, N., Naude, S. & Sithole, G., 2002, ‘Legislative issues impacting on the practice of the South African nurse practitioner’, Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 14(1), 11−15.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.2002.tb00064.x, PMid:11845634

Gillespie, B.M., 2007, ‘The predictors of resilience in operating room personnel’, Doctoral thesis, Griffith University, Australia.

Glantz, M.D. & Johnson, J.L. (eds.), 1999, Resilience and development: Positive life adaptations, University of Maryland, Baltimore: MD.

Goldberg, D.P. & Hillier, V.F., 1979, ‘A scaled version of the general health questionnaire’, Psychological Medicine 9(1), 139−145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700021644

Huber, C.H. & Mathy, R.M., 2002, ‘Focusing on what goes right: An interview with Robin Mathy’, Journal of Individual Psychology 58(3), 214−224.

Jackson, D., Clare, J. & Mannix, J., 2002, ‘Who would want to be a nurse? Violence in the workplace - A factor in recruitment and retention’, Journal of Nursing Management 10(1), 13−20.http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.0966-0429.2001.00262.x, PMid:11906596

Kaplan, H.B., 1999, ‘Toward an understanding of resilience: A critical review of definitions and models’, in M.D. Glantz & J.L. Johnson (eds.), Resilience and development: Positive adaptations, pp. 17-88, Kluwer Academic/Plenum, Dordrecht.

Keyes, C.L.M., 2002, ‘The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life’, Journal of Health and Social Research 43(2), 207−222.

Keyes, C.L.M., 2005, ‘The subjective well-being of America’s youth: Toward a comprehensive assessment’, Adolescent and Family Health 4(1), 3−11.

Keyes, C.L.M., 2006a, April, “If health matters: When will we stop saying one thing and doing another?” Keynote address presented at the South African Conference on Positive Psychology: Individual, social and work wellness, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 7 September 2006.

Keyes, C.L.M., 2006b, ‘Subjective well-being in mental health and human development research worldwide: An introduction’, Social Indicators Research 77(1), 1−10.

Keyes, C.L.M., 2007, ‘Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health’, American Psychologist 62(2), 95−108.

Keyes, C.L.M., 2009, ‘The nature and importance of positive mental health in America’s adolescents’, in R. Gilman, E.S. Huebner & M.J. Furlong (eds.), Handbook of positive psychology in schools, pp. 9−23, Routledge, New York.

Keyes, M.A., Sharma, A., Elkins, I.J., Iacona, W.G. & McGue, M., 2008, ‘The mental health of US adolescents adopted in infancy’, Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 162(5), 419−425.

Kinman, G., 2008, ‘Work stressors, health and sense of coherence in UK academic employees’, Educational Psychology, 28(7),823–835. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01443410802366298

Kleinke, C.L., 1998, Coping with the challenges, 2nd edn., Brooks Cole, Pacific Grove, CA.

Koen, M.P., Van Eeden, C. & Wissing, M.P., 2011, ‘The prevalence of resilience in a group of professional nurses’, Health SA Gesondheid 16(1), Art. #576, 11 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v16i1.576

Lazarus, R. & Folkman, S., 1984, Stress, appraisal and coping. Springer, New York.

Lifton, R.J., 1993, The protean self, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

London, M., 1993, ‘Relationship between career motivation, empowerment and support for career development’, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 66(1), 21−55.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1993.tb00516.x

Meredith, C., 2005, ‘Exploring resilience as a factor in student achievement’, Master’s thesis, Oxford University.

Mitchell, G.J., 2003, ‘Nursing shortage or nursing famine: Looking beyond numbers?’, Nursing Science Quarterly 16(3), 219−224.

Montazeri, A., Harirchi, A.M., Shariati, M., Garmaroudi, G., Ebadi M. & Fateh., A., 2003, ‘The 12-item General Health Questionnaire: Translation and validation in Iran’, Health and Quality of Health outcomes 1, 66.

Nelson, D. & Simmons, B., 2002, Health psychology and workstress: A more positive approach: Handbook of occupational health psychology, American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

Ntuli, A. & Day, C., 2004, Ten years on – Have we got what we ordered?, in P. Ijumba, C. Day & A. Ntuli (eds.), South African Health Review 2003/4 (pp. 1-10), Health Systems Trust, Durban.

Oulton, J.A., 2006, ‘The global nursing shortage: An overview of issues and actions’, Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice 7(3), 34−39.

Patterson, J.M., 2002, ‘Understanding family resilience’, Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(3), 233−246. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10019, PMid:11836706

Pelser, A.J., Ngwena, C.J. & Summerton, J.V., 2004, ‘The HIV/AIDS epidemic in South Africa: Trends, impacts and policy responses’, in H.C.J. van Rensburg (eds.), Health and health care in South Africa, pp. 109-170, Van Schaik, Pretoria.

Pillay, R., 2009, ‘Work satisfaction of professional nurses in South Africa: a comparative analysis of the public and private sectors’, Human resources for Health7, 15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-7-15, PMid:19232120, PMCid:2650673

Richardson, G.E., 2002, ‘Metatheory of resilience and resiliency’, Journal of Clinical Psychology 58(3), 307–321. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10020, PMid:11836712

Risher, H. & Stopper, W.G., 1999, ‘Current practices’, Human Resource Planning 22(2), 8−10.

Ryff, V.L. & Singer, B., 2003, ‘Thriving in the face of challenge: The integrative science of human resilience’, in F. Kessel & P.L. Rosenfield (eds.), Expanding the boundaries of health and social science: Case studies in interdisciplinary innovation, pp.181-205, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Scheier, M.F. & Carver, C.S., 1985, ‘Optimism, coping and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies’, Health Psychology 4(3), 219−247.

Scheier, M.F., Carver, C.S., & Bridges, M.W., 1994, ‘A re-evaluation of the Life Orientation Test’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67, 1063–1078.

Seligman, M.E.P., 1998, ‘The prediction and prevention of depression’, in D.K. Routh & R.J. DeRubeis (eds.), The science of clinical psychology: Accomplishments and future directions, pp. 201–214, American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

Seligman, M.E.P. & Csikszentmihalyi, M., 2000, ‘Positive psychology: An introduction’, American Psychologist, 55(1), 5−14.

Shaughnessy, J.J. & Zechmeister, E.B., 1997, Research methods in psychology, 4th edn., McGraw-Hill, New York.

Shisana, O., Hall, E.J., Maluleke, R., Chauveau, J. & Schawbe, C., 2004, ‘HIV/AIDS prevalence among South African health workers’, South African Medical Journal 94(10), 846–850.

Smit, R., 2004, ‘HIV/AIDS and the workplace: Perceptions of nurses in public hospitals in South Africa’, Journal of Advanced Nursing 5(1), 22–29.

Snyder, C.R., 2000, Handbook of hope, Academic Press, Orlando FL.

Snyder, C.R., Irving, L. & Anderson, J., 1991, ‘Hope and health’, in C.R. Snyder & D.R. Forsyth (eds.), Handbook of social and clinical psychology: The health perspective, pp. 285−305, Pergamon Press, Elmsford, New York.

South African Nursing Council, 2006, ‘SANC geographical distribution for 2006’, viewed 5 May 2007, from http://www.sanc.co.za/stats/stat2006

SPSS Inc., 2005, SPSS® 17.0 for Windows, Release 17.0.0, Copyright© by SPSS Inc.,1 Chicago, Illinois. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13803610500110174

Szelényi, K., Bryant, A.N. & Lindholm, J.A., 2005, ‘What money can buy: Examining the effects of prepaid monetary incentives on survey response rates among college students’, Educational Research and Evaluation 11, 385−404.

Tusaie, K. & Dyer, J., 2004, ‘Resilience: A historical review of the construct’, Holistic Nursing Practice 18(1), 3−10.

Van den Berg, H., Bester, C., Janse van Rensburg-Bonthuysen, E., Engelbrecht, M., Hlophe, H., Summerton, J., Smit, J., Du Plooy, S. & Van Rensburg, D., 2006, Burnout and compassion fatigue in professional nurses: A study in PHC facilities in the Free State, with special reference to the antiretroviral treatment program, University of Free State, Bloemfontein.

Vander Zyl, S., 2002, ‘Compassion fatigue and spirituality’, Nursing Matters 13(12), 4.

Van Rensburg, H.C.J. & Pelser, A.J., 2004, ‘The transformation of the South African Health System’, in H.C.J. van Rensburg (ed.), Health and health care in South Africa, pp. 109−170, Van Schaik, Pretoria.

Wagnild, G.M. & Young, H.M., 1993, ‘Development and psychometric evaluation of the resilience scale’, Journal of Nursing Measurement 1(2), 165−178.

Walker, H.J., 1999, ‘Clarifying the affective component of psychological well-being’, MA dissertation, Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education.

Walker, L. & Gilson, L., 2004, ‘We are bitter but we are satisfied: Nurse as street level bureaucrats in South Africa’, Social Sciences and Medicine 59(6), 1251−1265. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.020

Wissing, M.P. & Van Eeden, C., 2002, ‘Empirical clarification of the nature of psychological well-being’, South African Journal of Psychology 32(1), 32−44.

Wissing, J.A.B., Wissing, M.P., Du Toit, M.M. & Temane, Q.M., 2008, ‘Pychometric properties of Various Scales Measuring Psychological Well-Being in a South African Context: The FORT 1 Project’, Journal of Psychology in Africa 18(4), 511−520.

Zeidner, M. & Endler, N.S. (eds). 1996, Handbook of coping: Theory, research, applications, Wiley, New York.

|