|

An integrative literature review of identified scientific evidence, published from January 2000 to December 2008, of the utilisation of reflexology as complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) modalities to promote well-being and quality of life in adults with chronic diseases was done to facilitate nurses to give informed health education during comprehensive nursing care to patients with chronic diseases. Selected accessible databases were searched purposefully for research articles (N = 1171). Pre-set inclusion criteria were applied during the study selection process. The methodological study quality was reviewed and appraised with appropriate tools from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) and the American Dietetic Association’s (ADA) Evidence analysis manual (n = 21). Evidence extraction, analysis and synthesis of studies (n = 18) were done through the evidence class rating and level of strength as prescribed in the

manuals of ADA and CASP. Findings indicate statistically significant reduction in the frequency of seizures in patients with intractable epilepsy, an improvement of sensory and urinary symptoms associated with multiple sclerosis and clinically significant reduction of anxiety and pain in patients with cancer and fibromyalgia syndrome. These findings can be utilised by nurses to inform patients with these chronic diseases about alternative ways of treatment.

‘n Geïntegreerde literatuur oorsig van ge-identifiseerde wetenskaplike bewyse, gepubliseer vanaf Januarie 2000 tot Desember 2008, was gedoen oor die gebruik van refleksologie as aanvullende en alternatiewe behandelingsmodalitieit om welsyn en lewenskwaliteit te bevorder by volwassenes met kroniese siekte om verpleegkundiges te fasiliteer om ingeligte gesondheidsvoorligting te gee gedurende omvattende verpleegsorg aan pasiente met kroniese siektes. Geselekteerde toeganklike databasisse was doelbewustelik deursoek vir navorsingsartikels (N = 1171). Vooraf bepaalde insluitingskriteria was toegepas tydens die selekteringsproses. Die studie gehalte is nagegaan en beoordeel met toepaslike instrumente van die Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) en die American Dietetic Association (ADA) se Evidence analysis manual (n = 21). Bewys uitreksel, analisering en sintese van studies (n = 18) was gedoen

deur die bewysklas gradering en vlak van bewysterkte soos beskryf in die handleidings van ADA en CASP. Bevindings dui op ‘n statisitese beduidenisvolle verlaging in die frekwensie van konvulsies by pasiënte met epilepsie, ‘n verbetering van sensoriese en urinêre simptome ge-assosieer met veelvuldige sklerose en ‘n kliniese beduidenisvolle afname in angstigheid en pyn by pasiënte met kanker en fibromialgiese sindroom. Hierdie bevindings kan deur verpleegkundiges gebruik word om pasiente met hierdie kroniese siektes in te lig omtrent alternatiewe maniere van behandeling.

Anecdotal evidence claims potential health benefits of reflexology for patients with chronic diseases. In comprehensive nursing practice, nurses are often confronted with inquiries from patients regarding information on the accessibility of reflexology treatments, and the potential benefits of reflexology, therapeutic touch and acupuncture, as complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) modalities (Ebey-Tessendorf, Kretzmann & Mouton 1997:18; Lee, Charn, Chew & Ng 2004:658; Libster 2001:8; Mackereth, Dryden & Frankel 2000:17). Patients request advice on these CAM modalities and highly value the opinion of a trusted nurse in this regard; they expect nurses to be able to react informatively to these inquiries (Ebey-Tessendorf, Kretzmann & Mouton 1997:18; Libster 2001:8; Mackereth et al. 2000:17). However, it still appears to be unfamiliar territory to most nurses. The purpose of this study was therefore to explore and describe

identified scientific evidence on the utilisation of reflexology as CAM modality to promote well-being and quality of life in adults with chronic diseases. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee and Postgraduate and Research Committee of the School of Nursing Science at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University. No correspondence was embarked upon with authors of review articles.

Background

Reflexology is a CAM modality that entails a non-invasive therapeutic intervention. Reflexology is performed manually with the hands and fingers of the therapist to stimulate precision reflex points or zones on the feet, hands, face, ears or body of the individual. In this way existing vital energy or life force in the human body is balanced to promote health, vitality and well-being (Amster, Cogert, Lie & Scherger 2000:80; Dougans 2005:250–254; Libster 2001:121; Mackereth et al. 2000:70; Mackereth & Tiran 2002:5). Dougans (2005:20), an authority on reflexology, is of the opinion that reflexology offers a large scope of benefits to individuals who suffer from chronic diseases. Dougans (2005:11–13) explains that chronic diseases are the result of energy blockages, stagnancies and imbalances in the meridians of the human body. Chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus (DM), stroke and AIDS are relatively common in South Africa (Connor, Rheeder, Bryer, Meredith, Beukes, Dubb & Fritz 2005:334). In South Africa there appears to be an increase in chronic diseases and tuberculosis, especially in relation to the high incidence of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa (Bryer 2008:151; Connor et al. 2005:334; Modi, Modi & Mochan 2006:1247). Tuberculosis, cardiovascular disease and stroke place a tremendous burden on health care systems, especially in combination with the HIV and AIDS epidemic (Connor et al. 2004:627; Norman, Bradshaw, Schneider, Pieterse & Groenewald 2006:12). In South Africa, sedentary life style, smoking, obesity and alcohol abuse are of the most important lifestyle-related risk factors for chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension and cardiovascular disease (Bryer 2008:151–152; Groenewald, Vos, Norman, Laubscher, Van Walbeek, Sabojee, Sitas & Bradshaw 2007:674; Katz, Mdleleni, Shezi, Butler & Gerntholtz 2007:360). The symptoms of chronic diseases can be alleviated by conventional medicine and comprehensive health care, but place a high burden on health care provision. Furthermore, chronic deterioration often occurs, which places considerable stress on the individual’s energy, vitality and well-being (Smeltzer, Bare, Hinkle & Cheever 2008:167). Several studies have been conducted on the effectiveness of reflexology in various chronic diseases and there appears to be considerable anecdotal evidence and expert opinion in the literature on the benefits of reflexology in chronic diseases, but the question remains: what scientific evidence exists to guide evidence-based nursing practice in the giving out of information on reflexology as CAM modality? Carpenter and Neal (2005:116) recommended that more research be conducted on the utilisation and knowledge base of reflexology during chronic diseases to collect more evidence-based data. Reflexology, when used complementary to conventional health care may contribute to self empowerment in community-based healthcare of chronic diseases (Ebey-Tessendorf, Kretzmann & Mouton 1997:18; Lee et al. 2004:658; Libster 2001:8). The utilisation of reflexology in chronic diseases should therefore be explored, as there appears to be an increasing interest in complementing conventional care with reflexology during chronic diseases (Mackereth et al. 2000:66). Studies should include both quantitative and qualitative approaches to explore the total understanding and utilisation of reflexology as a holistic CAM modality during chronic diseases (Ebey-Tessendorf, Kretzmann & Mouton, 1997:20; Lee et al. 2004:655; Libster, 2001:121; Mackereth et al. 2000:66).

Objectives

This study is an exploration and description of identified scientific evidence of the utilisation of reflexology as CAM modality to promote well-being and quality of life in adults with chronic diseases:• to facilitate nurses with evidence based information regarding a complementary alternative treatment option

• to facilitate nurses on informed health education during comprehensive nursing care.

Research significance

An integrative literature review of recent identified scientific evidence of the utilisation of reflexology as CAM modality to promote well-being and quality

of life in adults with chronic diseases.

An integrative literature review was conducted that followed the steps of a systematic literature review to enhance rigour. The research method is therefore discussed according

to the steps of a systematic literature review.

Design

The research design used in this study is empirical as well as descriptive in nature. It is aimed at exploring and describing the identified scientific evidence of the utilisation of reflexology as CAM modality in the promotion of well-being and quality of life in adults living with a chronic disease. The study includes experimental and non-experimental studies to effectively include the holistic dimension of reflexology, demonstrated through the objective and subjective experience of clients and described by various authorities on reflexology

(Dougans 2005:13; Gillanders 2005:12; Mackereth & Tiran 2002:5).

Review question

The review question in a systematic review consists of specific components to focus the study as prescribed by Evans (2001:2) and Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt (2005:30). What evidence is available on the utilisation of reflexology as CAM modality

to promote well-being and quality of life in adults with chronic disease?

Search strategy (sampling)

A combination of databases was selected on the basis of appropriateness and accessibility. These databases were freely available and cover the field of CAM, nursing science and conventional medicine. Databases include Cochrane Library, EBSCOhost Platform, Google, ProQuest, SA Nexus, SaePublications, Science Direct and Web of Knowledge. Keywords such as complementary and alternative medicine, reflexology therapy, zone therapy and foot massage and combinations thereof were used in the search. The unit of analysis for this integrative literature review included all primary studies and reviews of primary studies on the utilisation of reflexology in adults living with a chronic disease published between January 2000 and December 2008. In order to standerdise reflexology treatment, duration of treatment was set to be at least 30 minutes and not more than 60 minutes in duration. In order to identify the most relevant, high-quality research that answers the review question appropriately, inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined, as adapted from the American Dietetic Association (ADA) (2005:13). The inclusion and exclusion criteria is displayed in Table 1.

Study selection

Study selection was conducted by an initial screening process of all titles and abstracts of identified studies to refine the search strategy and to determine relevancy to the review question. Accurate record keeping was conducted throughout the process for audit purposes to enhance rigour and is available on request, as described in the manual of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) (2009:23). The selection process of the relevant

studies (n = 21), for critical appraisal, is displayed in Figure 1.

Critical appraisal and evidence analysis

In the context of evidence-based practice, evidence from a high-quality, recent systematic review of randomised clinical trials (RCTs) is usually regarded as the strongest evidence on which to base decisions regarding efficiency (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt 2005:11). As the researcher departs from a naturalistic research paradigm, both recent experimental and non-experimental studies were included to explore and describe the utilisation of reflexology in adults with chronic disease, therefore critical appraisal is of major importance to select studies of good quality to answer the review question appropriately. A short list of selected studies was compiled for critical appraisal by the first author and independent reviewer. Study design was used to organise studies for appraisal of methodological quality regarding reliability, validity and credibility with appropriate tools of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). Thereafter each study was re-appraised by the first author and independent reviewer for the second time according to an evidence worksheet as recommended by the American Dietetic Association evidence analysis manual (ADA 2005:54). All worksheets were filed with the full-text article for audit purposes. The first author adapted and correlated the quality ratings of the CASP and the ADA evidence Analysis Manual with descriptive words to indicate high, medium and low methodological quality of appraised studies (ADA 2005:27–30; ADA 2008:42–46; CASP 2006)After critical appraisal a further three studies were excluded from data extraction and analysis of evidence to answer the review question due to low methodological quality. The first author re-appraised the included studies for evidence a third time with the criteria as recommended by the American Dietetic Association evidence analysis manual (ADA 2005:26–33; ADA 2008:42–46), to confirm methodological quality ratings and to check consistency in ratings of included studies for data extraction and analysis of evidence. The 2005 and 2008 editions of the ADA evidence analysis manuals were both consulted during critical appraisal.

Data extraction and data analysis

All the studies that were found to be of medium to high methodological quality after critical appraisal were included in the final sort list that was used for data extraction and data analysis of evidence to anwer the review question. This was done according to two steps, namely data reduction and data display. A summary of all the relevant studies was made according to study design, time span, sample, setting, data-collection instruments, statistical analysis, intervention or control strategy, evidence class, quality rating and bottom-line finding. The summary was created in table format for the sake of an effective display and to promote synthesis of evidence.

The summary for data extraction is displayed in Tables 2, 3 and 4.

Critical synthesis of data

After the data extraction and analysis was concluded and studies had been summarised, the data was critically synthesised by identifying appropriate variables. Seven variables emerged from the data analysis: time span and origin, samples and settings, data-collection instruments, data analysis, intervention versus control strategy, evidence class rating and bottom-line finding. These variables were examined closely to identify patterns, similarities, differences, conflicting evidence and relationships in relation to the review question. Synthesised evidence was classified and rated according to evidence class and level of strenght as prescribed in the American Dietetic Association evidence analysis manual (ADA 2005:17). Evidence from primary studies were classified and rated according to: • randomised controlled trials – the highest level of strength (class A)

• cohort studies – the second highest level of strength (class B)

• cross-sectional studies, case series, case reports and before-and-after studies – the fourth highest level of strength (class D). Collections of primary reports like meta-analysis and systematic reviews were classified and rated as class M evidence that were similar in level of strength than the randomised controlled trials of evidence class A. Therefore a conclusion statement was drawn according to the strength of synthesised evidence, similarities and the consistency in bottom-line findings.

|

TABLE 1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria with rationale for study selection.

|

|

TABLE 2: Data extraction of systematic reviews included for synthesis of evidence.

|

|

TABLE 3: Data extraction of experimental studies included for synthesis of evidence.

|

|

TABLE 4a: Data extraction of non-experimental studies included for synthesis of evidence.

|

|

TABLE 4b: Data extraction of non-experimental studies included for synthesis of evidence.

|

The included studies were reviewed for the evidence of utilisation of reflexology to promote well-being and quality of life in adults with chronic diseases. Bottom-line findings were consistent for the various diseases. There is statistically significant evidence (class M) in tersm of the effectiveness of reflexology to promote well-being and to improve sensory and urinary symptoms associated with multiple sclerosis (Wang, Tsai, Lee, Chang & Yang 2008). A primary experimental study (class A), supported the evidence of the systematic review (Siev-Ner, Gamus, Lerner-Geva & Achiron 2003). A statistically significant reduction in the frequency of seizures of patients with intractable epilepsy was reported by a primary experimental study of evidence class A (Dalal, Tripathi & Bajpai 2008).There is statistically no significant evidence (class M) in terms of efficacy of reflexology with cancer patients as reported by the systematic review (Wilkinson, Lockhart, Gambles & Storey 2008). However, statistically significant evidence of class A supported the utilisation of reflexology to decrease anxiety in patients with breast and lung cancer (Stephenson, Weinrich & Tavakoli 2000). Several other studies conducted on anxiety in cancer patient populations also reported a statistically significant decrease in anxiety after reflexology treatments (Hodgson & Andersen 2008; Quattrin, Zanini, Buchini, Turello, Annunziata, Vidotti, Colombatti & Brusaferro 2006; Stephenson, Swanson, Dalton, Keefe & Engelke 2007). An experimental study conducted by Hodgson (2000) on patients in the palliative stage of cancer who received reflexology treatments reported statistically significant improvements in pain management, decrease in constipation, better sleep, decreased anorexia and nausea. In evidence class D, Gambles reported on perceptions of patients in cancer palliative care after a course of reflexology treatments as experienced feelings of comfort, improved well-being and overall relaxation (Gambles, Crooke & Wilkinson 2002). This finding is consistent with the findings of experimental studies on the reduction of anxiety and pain in cancer populations. Furthermore, reflexology embodied emotional and spiritual healing effects in the body as experienced in relieving the symptoms of fibromyalgia syndrome in women by reducing pain and increasing overall well-being as reported by a non-experimental case study in evidence class D (Gunnarsdottir 2007). This finding is consistent with the findings of experimental studies on the reduction of anxiety and pain in cancer populations. Reflexology has no statistically significant superior effects over effleurage massage in the improvement of pain management in diabetic neuropathy, however, both interventions clinically improved the pain of diabetic neuropathy. This was reported by a randomised split-plot factorial design and falls in evidence class A (Kulik 2002). There is no statistically significant evidence (class A) that reflexology had any benefit for patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) regarding bloatedness, abdominal pain and constipation and/or diarrhoea (Tovey 2002). There is no statistically significant evidence (class A) that reflexology had been more effective than non-specific foot massage in the treatment of physical and psychological symptoms of menopause. The improvements that were encountered in both groups in the study, might have been due to non-specific factors (Williamson, White, Hart & Ernst 2002). There is no statistically significant evidence (class A) that reflexology has a specific effect on asthma beyond the placebo effect (Brygge, Heinig, Collins, Ronborg, Gehrchen, Hilden, Heegaard & Poulsen 2001).

The active participation of western countries, such as the United States of America, to conduct good quality research on the utilisation of reflexology in adults with chronic disease is notable. An overall heterogeneity was displayed in samples, settings and chronic diseases during the data extraction of the primary studies included for evidence analysis. The primary studies made use of non-probability sampling and purposive sampling that were appropriately for design. The sample sizes of the experimental studies were relative small and therefore lead to limitations during statistical analysis. Randomisation of subjects to intervention and control groups was followed in all experimental studies to counteract confounding variables. The control intervention strategy mostly used in the experimental primary studies was non-specific foot massage avoiding specific reflex points and reflex areas on the feet of subjects or participants. The reflexology intervention was standardised in all of the primary studies.A tendency was noted towards favouritism in the utilisation of the experimental design, outcomes of the primary experimental studies related thus more to the efficacy of reflexology, whilst the outcomes of the primary non-experimental studies related more to in depth individualised experience of emotional and spiritual healing effects of reflexology. Reflexology as a holistic CAM modality could be more favoured by a mixed research design that incorporate both the effectiveness of treatment as well as emotional and spiritual healing effects. Similarities across findings of the included primary studies for evidence analysis were assessed according to methodological quality ratings, classes of evidence, levels of strenght , consistency in findings, clinical impact of findings and generalisability of findings. Experimental studies (n = 14) were all of evidence class A with neutral methodological quality ratings, which influenced the strenght of evidence negatively, whilst the two systematic reviews were of evidence class M, both with high methodological quality ratings that contribute positively to the strenght of evidence. The two primary studies with non-experimental designs differed in methodological quality ratings of high and neutral respectively, which limit the strenght of evidence accordingly. Consistencies in findings across several independent primary studies support positive benefits of reflexology on improving sensory symptoms and urinary symptoms, decreasing anxiety and improve pain management in chronic disease. However, some doubts were raised about statistical and clinical significance of the effect size in a few experimental studies (Hodgson & Andersen 2008; Quattrin et al. 2006; Stephenson et al. 2007). Strength of evidence is influenced by the magnitude of effect and the importance of studied outcomes as discussed in the manual of ADA (2009:57). The clinical impact of the evidence in this study is therefore negatively influenced.

Bottom-line findings were consistent across most of the primary studies with a difference in outcome regarding three detached experimental primary studies on Irritable Bowel Syndrome, menopausal symptoms and asthma (Tovey 2002; Williamson et al. 2002; Brygge et al. 2001). The conflicting evidence was disclosed in experimental studies with a neutral methodological quality rating and a different chronic disease typology in each case. No validations were made in follow-up studies, viewed that some of the studied outcomes were intermediate outcomes directly related to the current review question.The conflicting evidence is therefore handled with caution, awaiting future studies for validation of findings.Chronic diseases is a collective noun for a wide scope of different diseases that share the common ground of chronically impairment in physical vitality, subjective feelings of un-wellness and deficits in quality of life. The bottom line findings of the reviewed studies were therefore in correlation with chronic diseases as collective noun although the evidence analysis consisted of different chronic diseases per se.

Limitations

Methodology limitations of small sample sizes, heterogeneity in settings and various chronic disease typologies of the included primary studies of experimental design had a very negative influence on the generalisability of the findings and contextualisation to the South African context as such. The review question was answered appropriately, however the integrative literature review was conducted on studies presenting mostly with a neutral quality rating (class A) and a mix of class A, M and D evidence; therefore, generalisation is limited to the specific context and cannot be generalised to the wider population or South African context. Therefore generalisability should be treated with caution till further studies have been conducted with more rigorous methodology and larger sample

sizes to contribute positively to the effect size.

Nursing practice

Reflexology as a CAM modality may be incorporated into nursing practice to make it more accessible to patients with chronic disease or disabilities or those undergoing palliative care to promote well-being and quality of life. Patients should be informed of the possible benefits and left to decide for themselves if they want to utilise it as part of emotional and spiritual healing

to empower themselves in their pursuit towards wholeness and integrity.

Nursing education

Nurses should be facilitated on reflexology as CAM modality to respond proactively on patients inquiries and to enable informed

health education in comprehensive nursing care of chronic diseases.

Nursing research

Future research with appropriate design and a holistic approach is recommended to confirm and validate the findings of this study

to facilitate the knowledge base of comprehensive nursing care.

The author drew the final conclusion statement from the findings of variables, emerging patterns, similarities, differences, possible relationships amongst the variables and by using the recommended grading table of the ADA evidence analysis manual (ADA 2005:44–45; ADA 2008:63). What evidence is available on the utilisation of reflexology as CAM modality to promote well-being and quality of life in adults with chronic disease? There is fair evidence that reflexology as CAM modality improves well-being and quality of life in adults living with chronic diseases as demonstrated through statistically significant reduction in intractable epileptic seizures, improved sensory and urinary symptoms associated with multiple sclerosis, a clinically significant decrease in anxiety associated with cancer patients during palliative care, improved relaxation, coping and well-being in cancer patients during palliative care; and reduction in pain together with improvement in overall well-being in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Reflexology is a holistic CAM modality that treats the patient as individual in a unique way to balance underlying energy imbalances and synchronise the body to its own emotional and spiritual healing mechanism to actively pursue wholeness and integrity on physical, psychological and social level. Reflexology appears to be a non-invasive therapy with no reported adverse effects that may promote well-being and quality of life in adults with chronic disease. A fair amount of evidence appears in scientific literature that reflexology is effective in some chronic diseases, however, more integrative and high quality research are needed to verify and validate the findings of this study in order to generalise it to the South African context.

The authors of this article would like to thank the National Research Foundation (NRF) for their financial assistance, as well as Thuthuka for assistance in obtaining a bursary to complete the masters studies. The authors would also like to acknowledge

Wilma Ten Ham as independent reviewer of data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s)

which may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors’ contributions

BS was the supervisor of the study. E.S. (North-West University) performed all data collection and wrote the manuscript. B.S. (North-West University) helped with data analysis as independent reviewer; C.v.d.W.

(North-West University) was the co-supervisor of the study.

ADA see American Dietetic Association.American Dietetic Association, 2005, ADA Evidence Analysis Manual, American Dietetic Association, Chicago. American Dietetic Association, 2008, Evidence Analysis Manual: Steps in the ADA Evidence Analysis Process,

American Dietetic Association, Chicago. Amster, M.A., Cogert, G., Lie, D.A. & Scherger, J.E., 2000, ‘Attitudes and use of complementary and

alternative medicine by California family physicians’, The International Journal on Grey Literature 1(2), 77−81.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14666180010371781

Bryer, A., 2008, ‘Time is brain’ and stroke units: stroke care today’, SA Journal of Diabetes &

Vascular Disease 5(4), 151−153. Brygge, T., Heinig, J.H., Collins, P., Ronborg, S., Gehrchen, P.M., Hilden, J., Heegaard, S. & Poulsen,

L.K., 2001, ‘Reflexology and bronchial asthma’, Respiratory Medicine 95, 173−179. CASP see Critical Appraisal Skills Programme.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/rmed.2000.0975,

PMid:11266233

Carpenter, J.S. & Neal, J.G., 2005, ‘Other complementary and alternative medicine modalities: Acupuncture, magnets, reflexology, and homeopathy’, The American Journal of Medicine 18(12), 109−117.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.058,

PMid:16414335

Centre For Reviews and Dissemination, 2009, Systematic Reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care,

University of York, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Cline, M.E., Herman, J., Shaw, E.R. & Morton, R.D., 1992, ‘Standardization of the visual analogue scale’, Nursing Research 41, 378−380.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006199-199211000-00013

Connor, M.D., Neurol, F.C., Dhorogood, M., Casserly, B., Dobson, C., Warlow, C.P., 2004, ‘Prevalence of Stroke Survivors in Rural South Africa’, Stroke 35, 627−632.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000117096.61838.C7,

PMid:14963282

Connor, M.D., Rheeder, P., Bryer, A., Meredith, M., Beukes, M., Dubb, A. & Fritz, V. 2005, ‘The South African

Stroke Risk in General Practice Study’, South African Medical Journal 95(5), 334−338 May.

PMid:15931448

Crane, B., 1997, Reflexology: The Definitive Practitioner’s Manual, London, Element Books Limited. CRD see Centre for Reviews and Disseminations. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2006, Evidence-based Health Care, Oxford, Public Health Resource Unit, viewed

24 December 2008, from http//www.phru.nhs.uk/casp/critical_appraisal_tools.htm Dalal, K., Tripathi, M. & Bajpai, V., 2008, ‘Randomized clinical trial of a combination of reflexology

therapy and conventional drug therapy versus the drug therapy alone, in the management of intractable therapy’,

Epilepsia 49(7S), 1−498. Dougans, I., 2005, Reflexology the 5 elements and their 12 meridians a unique approach, London, Thorsons. Ebey-Tessendorf, Kretzmann, G. & Mouton, N., 1997, ‘Expanding the boundaries of the nursing curriculum:

should alternative medicine be included’, Health SA, Gesondheid SA 2(1), 17−21. Evans, D., 2001, ‘An introduction to Systematic Reviews’, Changing Practice: Evidence Based

Practice information Sheets for Health Professionals 2(1), 1−6. Gambles, M., Crooke, M. & Wilkinson, S., 2002, Evaluation of a hospice based reflexology service: a qualitative audit of patient perceptions, European Journal of Oncology Nursing 6(1), 37−44.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1054/ejon.2001.0157,

PMid:12849608

Gillanders, A., 2005, The Family Guide to Reflexolog, London, Gaia Books Ltd. Groenewald, P., Vos, T., Norman, R., Laubscher, R., Van Walbeek, C., Sabojee, Y., Sitas, F. & Bradshaw, D.,

2007, ‘Estimating the burden of disease attributable to smoking in South Africa in 2000’, South

African Medical Journal 97(8), 674−681.

PMid:17952224

Gunnarsdottir, T.J., 2007, ‘Reflexology for Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A case study’, PhD thesis, Faculty

Graduate School, University of Minesota. Hodgson, H., 2000, ‘Does reflexology impact on cancer patients’ quality of life?’,

Nursing Standard 14(31), 33−38. Hodgson, N.A. & Andersen, S., 2008, The Clinical Efficacy of Reflexology in Nursing Home Residents with Dementia, The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 14(3), 269−275.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/acm.2007.0577,

PMid:18370580

Holmes, S. & Dickerson, J., 1987, ‘The quality of life: design and evaluation of a self-assessment instrument for

use in cancer patients’, International Journal of Nursing Studies 24, 15−24.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0020-7489(87)90035-6

Katz, I., Mdleleni, G., Shezi, E.Z., Butler, O. & Gerntholtz, T., 2007, ‘The burden of chronic

kidney disease is increasing, along with other chronic diseases’, CME – Your SA journal of CPD 25(8), 360−362. Khan, K.S., Kunz, R., Kleijnen, J. & Antes, G., 2003, ‘Five steps to conducting a systematic

review’, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 96(3), 118−121.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.96.3.118

Kruger, A., 2009, Personal communication with the author, Potchefstroom, North-West University Potchefstroom Campus.Kulik, D., 2002, ‘Reflexology and massage in the treatment of type II diabetic neuropathy’,

Masters thesis, University of the Pacific. Lee, G.B.W., Charn, T.C., Chew, Z.H. & Ng, T.P., 2004, ‘Complementary and alternative

medicine use in patients with chronic diseases in primary care is associated with perceived quality of care and cultural beliefs’, Family Practice 21(6), 654−660.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmh613,

PMid:15531625

Libster, M., 2001, Demonstrating Care. The Art of Integrative Nursing, United States of America, Thomson Learning. Mackereth, P., Dryden, S.L. & Frankel, B., 2000, ‘Reflexology: Recent research approaches’, Complementary Therapies in Nursing and Midwifery 6, 66−71.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1054/ctnm.2000.0458,

PMid:10844743

Mackereth, P.A. & Tiran, D., 2002, Clinical Reflexology: A guide for Health Professionals, Edinburgh, Churchill Livingstone. Melnyk, B.M. & Fineout-Overholt, E., 2005, Evidence-based practice in Nursing and Healthcare: A guide to best practice,

Philadelphia, Lippencott Williams & Wilkins. Melzack, R., 1987, ‘The short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire: Major properties and scoring methods’,

Pain 30, 191−197.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959 (87)91074-8

Modi, G., Modi, M., Mochan, A., 2006, ‘Stroke and HIV – Causal or coincidental co-occurrence?’

South African Medical Journal 96(12), 1247−1248.

PMid:17252152

NEUD see New English Usage Dictionary New English Usage Dictionary, 2001, Pretoria, Pinetown Printers (Pty) Ltd. Norman, R., Bradshaw, D., Schneider, M., Pieterse, D. & Groenewald, P., 2006, Revised Burden

of Disease Estimates for the Comparative Risk Factor Assessment, South Africa 2000, Methodological Note, Cape Town,

South African Medical Research Council. Poole, H., Glenn, S. & Murphy, P., 2007, ‘A randomized controlled study of reflexology for the management of chronic low back pain’, European Journal of Pain II, 878−887.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.01.006,

PMid:17459741

Quattrin, R., Zanini, A., Buchini, S., Turello, D., Annunziata, M.A., Vidotti, C., Colombatti, A. & Brusaferro, S., 2006, ‘Use of reflexology foot massage to reduce anxiety in hospitalized cancer patients in chemotherapy treatment: methodology and outcomes’, Journal of Nursing Management 14, 96−105.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2934.2006.00557.xc,

PMid:16487421

Quinn, F., Hughes,C.M. & Baxter, G.D., 2008, ‘Reflexology in the management of low back pain: A pilot randomized controlled trial’, Complementary Therapies in Medicine 16, 3–8.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2007.05.001,

PMid:18346622

Siev-Ner, I., Gamus, D., Lerner-Geva, L. & Achiron, A., 2003, ‘Reflexology treatment relieves symptoms of multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled study’, Multiple Sclerosis 9, 356−361.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1352458503ms925oa,

PMid:12926840

Smeltzer, S.C., Bare, B.G., Hinkle, J.L. & Cheever, K.H., 2008, Brunner and Suddarth’s Textbook of Medical-Surgical Nursing, 11th edn., Philadelphia, Lippencott Williams & Wilkins. Stephenson, N., Dalton, J. & Carlson, J., 2003, ‘The effect of foot reflexology on pain in patients with Metastatic Cancer’, Applied Nursing Research 16(4), 284−286.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2003.08.003,

PMid:14608562

Stephenson, N.L.N. & Dalton, J.A., 2003, ‘Using reflexology for pain management’, Journal of Holistic Nursing 21(2), 179−191.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2003.08.003,

PMid:14608562

Stephenson, N.L.N., Swanson, M., Dalton, J., Keefe, F.J. & Engelke, M., 2007, ’Partner-Delivered Reflexology: Effects on Cancer Pain and Anxiety’, Oncology Nursing Forum 34(1), 127−132.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1188/07.ONF.127-132,

PMid:17562639

Stephenson, N.L.N., Weinrich, S.P. & Tavakoli, A.S., 2000, ‘The effects of foot reflexology on anxiety

and pain in patients with Breast and Lung Cancer’, Oncology Nursing Forum 27(1), 67−72.

PMid:10660924

Tovey, P., 2002, ‘A single-blind trial of reflexology for irritable bowel syndrome’, British Journal of

General Practice 52, 19−23.

PMid:11791811,

PMCid:1314196

Wang, M-Y., Tsai, P-S., Lee, P-H., Chang, W-Y. & Yang C-M., 2008, ‘The efficacy of reflexology: Systematic review’, Journal of Advanced Nursing 62(5), 512−520.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04606.x,

PMid:18489444

Ware, J.E. & Sherbourne, C.D., 1992, ‘The MOS 36 item short form health survey (SF-36): Conceptual framework and item selection’, Medical Care 30, 473−483.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002,

PMid:1593914

Wilkinson, I.S.A., Prigmore, S. & Rayner, F., 2006, ‘A randomised-controlled trial examining the effects of reflexology of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)’, Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 12, 141−147.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2005.10.004,

PMid:16648092

Wilkinson, S., Lockhart, K., Gambles, M. & Storey, L., 2008, ‘Reflexology for symptom relief in patients with cancer’, Cancer Nursing 31(5), 354−360.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.NCC.0000305756.58615.81,

PMid:18772659

Williamson, J., White, A., Hart, A. & Ernst, E., 2002, ‘Randomised controlled trial of reflexology for menopausal symptoms’, BJOG: British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 109, 1050−1055.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002. 01504.x

|

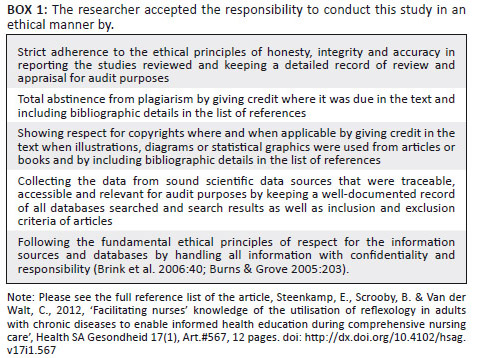

Box 1: The researcher accepted the responsibility to conduct this study in an

ethical manner by.

|

|

|